This Guy’s So Bad He’s Almost Good For Us

The positive power of a negative example

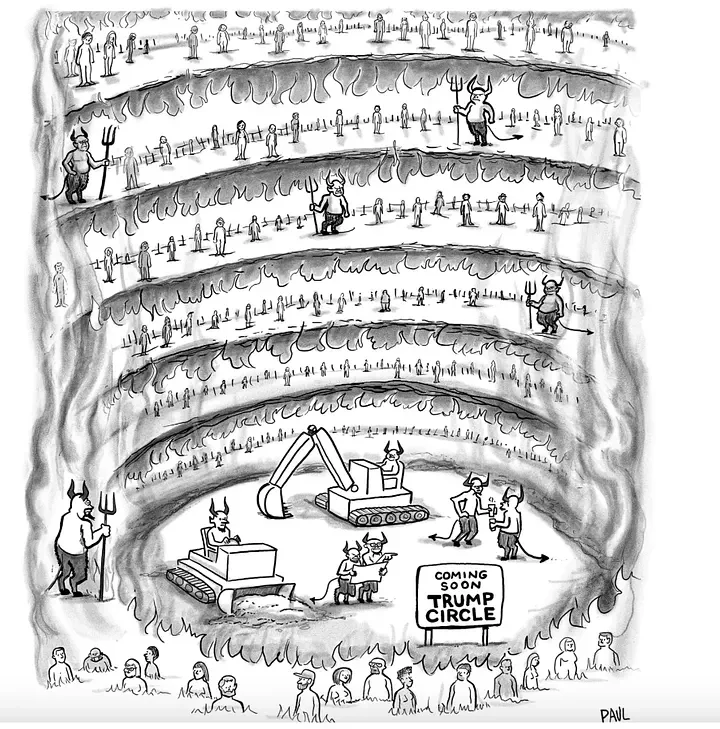

Under construction: The White House East Wing. Courtesy of The New Yorker

For the past few years, I’ve had a recurring dream. Donald Trump is standing among us in his irredeemably wounded pride while we recoil in horror and disgust. Then suddenly, he lifts his bruised hand to the side of his scowling face and rips off the mask we didn’t realize he was wearing.

“Don’t you see?” he exclaims. “I had to be just this bad to get you all to wake up to the good in you!”

It’s like that memorable line from Joni Mitchell: “Don’t it always seem to go that you don’t know what you got till it’s gone.”

Of course, he is just this bad, and for no reason other than his own incurable inner torment. To escape his self-created hell, he torments others but gets no lasting satisfaction. Yet there is something to the truth that we humans are often moved to remember and revive our better selves not so much by the examples of the saints among us as by the devils (who are themselves, after all, fallen angels).

Let’s face it: we live in a far from perfect union and always have. In recent decades, we’ve allowed the worst among us to systematically undermine the foundations of our freedom and democratic institutions. It’s as if our civic immune systems — a flawed democratic process, the rule of law, and public participation in the political process — have been relentlessly attacked and disabled, weakening our capacity to fend off tyranny. Our collective failure to safeguard our rights and freedoms has left us unprotected from the lethal cancers of corruption, greed, and extreme inequality.

Sound familiar? Our physical immune system has failed more than once before, most recently in the scourge of AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) that has killed 44 million people since the epidemic began. It would have killed many more, but antiretroviral therapy slowed its spread. The best defense against physical disease turns out to be a strong immune system. And a crucial part of a robust immune system is a resilient spirit that can help turn disease into healing.

The 2,700 October 18 No Kings events were demonstrations of this kind of resilience at the societal level. They mark a new collective invention in the history of nonviolence. Think about it for a moment: nonviolence is a double negative. It says what it’s not, but not what it is. No Kings demonstrated something more powerfully positive — our capacity for renewal and reconnection. The Trump machine had set a trap for us, predicting massive violence that would then justify militarized repression. We not only didn’t give them that excuse. We turned our gatherings into festivals of affirmation, appreciation, and even joy. Who knew that one of the best antidotes to tyranny and the rage it embodies is cherishing the world and each other just for the imperfect beings we are?

As a battle-tested Sixties demonstrator, I experienced both the exhilaration of gathering in the streets with kindred spirits and the strife of being jeered by legions of counter-demonstrators. Many denounced us as traitors. Eventually, we ourselves were consumed by frustration that we couldn’t stop the war. The war did, however, eventually end, and our movements were a part of that change.

Yet on October 18, despite the regime’s and media’s depictions of the current moment as one of extreme polarization, there were few if any counter — protesters at the No Kings demonstrations. Instead, hundreds of passing vehicles in every city and town signaled their support with choruses of car horns. Maybe we’re not after all quite as polarized as we’re made out to be. Contrary to the story peddled by those in whose interest it is to divide us, day to day, moment after moment, we actually get along pretty well.

So what positive role could this would-be dictator’s extreme malfeasance possibly play in reawakening our long-dormant civic immune systems? Well, he is an equal opportunity destroyer, aiming to demolish anything and everything of value left in this country. In the process, he and his minions are inflicting maximum pain even on his own supporters. In that sense, they are increasingly uniting us in opposition to their criminality in ways that no more affirmative leader could accomplish.

During the uprisings in Soviet-dominated Eastern Europe in 1989, parties long opposed to one another came together to overthrow the moribund regimes that had so long oppressed them. Air war strategists have found that bombing a populace from the air, as in London during the Blitz and in Hanoi during the Vietnam war, actually achieves the opposite of its intended effect. It unites those who would never have cooperated in more normal times. As North Vietnam’s minister of education told me during my visit in 1968, “This is the easy part. Once the war is over, we’ll go back to fighting among ourselves.”

Reawakening our civic immune systems might just lead to a new reform movement after the fall of this regime. It has happened more than once in American history. The temptations of tyranny will always be with us. Corruption, criminality, and the will to power are endemic to human societies. But they aren’t all of who we are. By no means. Politics can’t be understood without a healthy appreciation for irony. As in the rest of nature, where for every action there is an equal and opposite reaction, the most destructive events often trigger the most constructive responses.

So while Donald Trump is most likely not just wearing a mask that cloaks a saving grace, what we do in response to his manifest evil to rescue all that still matters to us will make all the difference in redeeming a world worth cherishing.